Reviews:

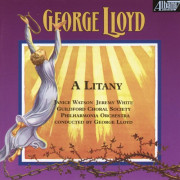

Lloyd's latest work is a choral setting in four movements of words from John Donne's 28-verse poem "A Litany" Though Donne is a well-loved poet, this is not a well-known poem, and Lloyd takes just twelve verses for his four movements, in which he also asks for soprano and baritone soloists.

Commissioned by the Guildford Choral Society, it was premiered by them with the Philharmonia Orchestra and the ever-young 83-year old composer conducting on Saturday 16 March. (At the Festival Hall my stopwatch timings for the movements were: 12'48"; 13'22"; 6'58"; 19'46".) The recording for Albany by the same forces took place the following weekend at Watford Town Hall (now renamed the Colosseum!). A colder wind may be felt in this work than in some of his previous scores, yet Lloyd's optimism keeps breaking through, and as he tells us in his note in the vocal score:

"In spite of John Donne's catalogue of human frailties and disasters there are verses in the poem that give some hope, and these are the verses I have used to end the work". The composer's ending is in his most exciting orchestrally brilliant vein. The audience loved it. There are two soloists: a soprano (Janice Watson) who appears in the second and fourth movements, and a baritone in the first, second and fourth. The baritone, a dramatic and complex part, was given strong characterisation at the Festival Hall by the ever versatile David Wilson-Johnson, though he was often battling against considerable volumes of orchestral sound. The Festival Hall was a splendid venue, yet it is a cruelly analytical and unsympathetic acoustic, especially for performers unused to its lack of resonant ambience, and this surely accounted for any failings. In the hall the orchestra seemed to have the upper hand and the balance was not good in the loudest moments, particularly in the last movement. Janice Watson projected the largely reflective soprano part with poise yet in the noisy closing pages punched her sustained top Cs throughout the texture in thrilling style. The recording session, in the far kinder acoustic at Watford, the following weekend, underlined the delights of the work, surely to become one of its composer's most popular. It also allowed the choir to demonstrate their mastery of the music. a case in point is the a capella slow movement, which at the RFH, seemed cold, now acquired an engaging radiance. It is a piece destined to cause choirs some pitching problems, but possibly may emerge as a movement worth performing separately. I would love to hear it in the Guildford choir's home stamping ground of Guildford Cathedral.

Various commentators drew parallels between Lloyd's approachable idiom and earlier composers, but the personal fingerprints are writ so large there are few moments of close parallel. To my mind the most striking one is in the second movement when the xylophone sets up an insistent semiquaver skirling, momentarily strikingly reminiscent of a similar texture in Havergal Brian's Gothic Symphony. The second movement, with its contrasting fast and more reflective music, was particularly rewarding, the soprano's "Ah, blessed glorious Trinity" such a simple invention, yet wonderfully effective, and the quiet ending, magical. The extended final movement is a classic Lloyd structure and if you enjoyed his Symphonic Mass you will not be disappointed.

This is a work of bold gestures and juxtaposed primary colours. This was underlined by the composer at the recording, constantly asking the singers to make the music more dramatic, asking the strings to sing more, the players for more vibrant tone. At the Festival Hall the Philharmonia cellos were notably warm, particularly rewarding in a passage near the beginning, a striking harbinger of what was to come.

CD promised for October. Lewis Foreman, The British Music Society Magazine

A major new choral work - intensely committed singing, generous tunes. The choral writing grows increasingly ecstatic. A paean of confidence. The Daily Telegraph

Commissioned by the Guildford Choral Society, it was premiered by them with the Philharmonia Orchestra and the ever-young 83-year old composer conducting on Saturday 16 March. (At the Festival Hall my stopwatch timings for the movements were: 12'48"; 13'22"; 6'58"; 19'46".) The recording for Albany by the same forces took place the following weekend at Watford Town Hall (now renamed the Colosseum!). A colder wind may be felt in this work than in some of his previous scores, yet Lloyd's optimism keeps breaking through, and as he tells us in his note in the vocal score:

"In spite of John Donne's catalogue of human frailties and disasters there are verses in the poem that give some hope, and these are the verses I have used to end the work". The composer's ending is in his most exciting orchestrally brilliant vein. The audience loved it. There are two soloists: a soprano (Janice Watson) who appears in the second and fourth movements, and a baritone in the first, second and fourth. The baritone, a dramatic and complex part, was given strong characterisation at the Festival Hall by the ever versatile David Wilson-Johnson, though he was often battling against considerable volumes of orchestral sound. The Festival Hall was a splendid venue, yet it is a cruelly analytical and unsympathetic acoustic, especially for performers unused to its lack of resonant ambience, and this surely accounted for any failings. In the hall the orchestra seemed to have the upper hand and the balance was not good in the loudest moments, particularly in the last movement. Janice Watson projected the largely reflective soprano part with poise yet in the noisy closing pages punched her sustained top Cs throughout the texture in thrilling style. The recording session, in the far kinder acoustic at Watford, the following weekend, underlined the delights of the work, surely to become one of its composer's most popular. It also allowed the choir to demonstrate their mastery of the music. a case in point is the a capella slow movement, which at the RFH, seemed cold, now acquired an engaging radiance. It is a piece destined to cause choirs some pitching problems, but possibly may emerge as a movement worth performing separately. I would love to hear it in the Guildford choir's home stamping ground of Guildford Cathedral.

Various commentators drew parallels between Lloyd's approachable idiom and earlier composers, but the personal fingerprints are writ so large there are few moments of close parallel. To my mind the most striking one is in the second movement when the xylophone sets up an insistent semiquaver skirling, momentarily strikingly reminiscent of a similar texture in Havergal Brian's Gothic Symphony. The second movement, with its contrasting fast and more reflective music, was particularly rewarding, the soprano's "Ah, blessed glorious Trinity" such a simple invention, yet wonderfully effective, and the quiet ending, magical. The extended final movement is a classic Lloyd structure and if you enjoyed his Symphonic Mass you will not be disappointed.

This is a work of bold gestures and juxtaposed primary colours. This was underlined by the composer at the recording, constantly asking the singers to make the music more dramatic, asking the strings to sing more, the players for more vibrant tone. At the Festival Hall the Philharmonia cellos were notably warm, particularly rewarding in a passage near the beginning, a striking harbinger of what was to come.

CD promised for October. Lewis Foreman, The British Music Society Magazine

A major new choral work - intensely committed singing, generous tunes. The choral writing grows increasingly ecstatic. A paean of confidence. The Daily Telegraph

'A Litany' celebrates the English choral tradition as confidently as Parry, Elgar and Vaughan Williams.

The Financial Times

The Financial Times

'Unmusical' is such an old-fashioned and discredited term to use as criticism of Donne's verse that one hardly dares to venture it, even though some such observation cries out for release throughout a reading of the 28 stanzas of A Litany. The deliberate steps of argument, with explanatory qualifications and parentheses, almost obstinately obstruct a lyrical or rhapsodic flow. Yet that (lyrical flow is just the style of George Lloyd's music, and especially of his writing for voices. A strange disparity of style in text and setting makes it hard to accept the work on its own terms, yet if one simply listens to sound there may be much to enjoy. Enjoyment is clearly an aim (perhaps the primary aim) in view. Here is a composer who knows what he himself likes, and is not going to write differently because the trend of the times is against him. Besides, he probably suspects that what he likes is what a majority of the listening public likes too, except that it is intimidated by modern orthodoxy into denying it. The public thus addressed is not exactly one for which music ended with Puccini's last opera but it is one that might be happier had Turandot been a stop along the line rather than a terminus. That opera is certainly evoked in the first movement of this new work, and it is to be feared that the "overtones from the East" which the composer finds in Donne's poems, will be associated in the minds of most of his listeners with the Pekin of Pu-tin-Pao rather than with the mysticism of the Tao. How successful a work it is I would not care to say; but this is a première recording and it earns a welcome. The piece was commissioned by the Guildford Choral Society, who sang in its first performance at London's Royal Festival Hall in March of this year, and who now on this record sing it again with confidence and apparent zest. They are certainly kept busy throughout its four substantial movements, which in the forces used (with soprano and baritone soloists) have something in common with Vaughan Williams' Sea Symphony. All the singers involved must have been grateful to find that the voice-parts are written as for singers rather than vocal instrumentalists. Of the soloists a good deal is demanded but it all lies within the natural scope of the voice, without jagged intervals or excessive use of upper and lower extremities. Janice Watson and Jeremy White contribute with feeling and assurance, though the soprano part would probably benefit from a more ample volume and the baritone from a voice of finer texture. The orchestral score, rich in colour and varied in resources, is royally served by the Philharmonia, and, with the 83-year-old composer in charge, the well-recorded performance carries all the conviction proper to a man who writes as he likes, irrespective of fashion. JBS Gramophone