Tuning Up No 1: September 2021

No 1: George Lloyd and music’s healing powers

by Peter Davison

As the drama of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic plays out, there is more discussion than ever about the therapeutic value of the arts, especially applied to our mental health. The evidence shows beyond question that the arts are good for our well-being. Music in particular has a unique capacity to soothe the troubled mind by helping us access long-buried memories, feelings and emotions, as well as providing templates that are able to give them order.

Among British composers of the last century, few have illustrated music’s healing powers better than George Lloyd (1913-1998). Lloyd was a prodigy, whose Cornish fairy opera Iernin was first performed on the London stage in 1934, when he was only 21 years old. The work attracted the praise of several major figures in British musical life, including Vaughan-Williams and Thomas Beecham. However, after the onset of the Second World War, the young composer joined the Royal Marines in 1941 as a bandsman, and soon he was posted to convoy duty on the HMS Trinidad. Lloyd had soon written the ship's march, which his fellow bandsmen played to raise the crew’s morale.

George Lloyd (left) with Royal Marine Bandsmen, Plymouth 1941

George Lloyd (left) with Royal Marine Bandsmen, Plymouth 1941

On 29 March 1942, in the Arctic waters near Murmansk, a terrible accident occurred when the ship came under fire from three enemy destroyers. After setting one destroyer on fire, HMS Trinidad torpedoed herself, blowing a large gash in the hull and rupturing the oil tanks. Lloyd was lucky to escape with his life from the flood of black oil that engulfed his position below deck, where 17 of the 21 men were killed, including 9 of his colleagues in the Royal Marine Band. (The full story can be found here.)

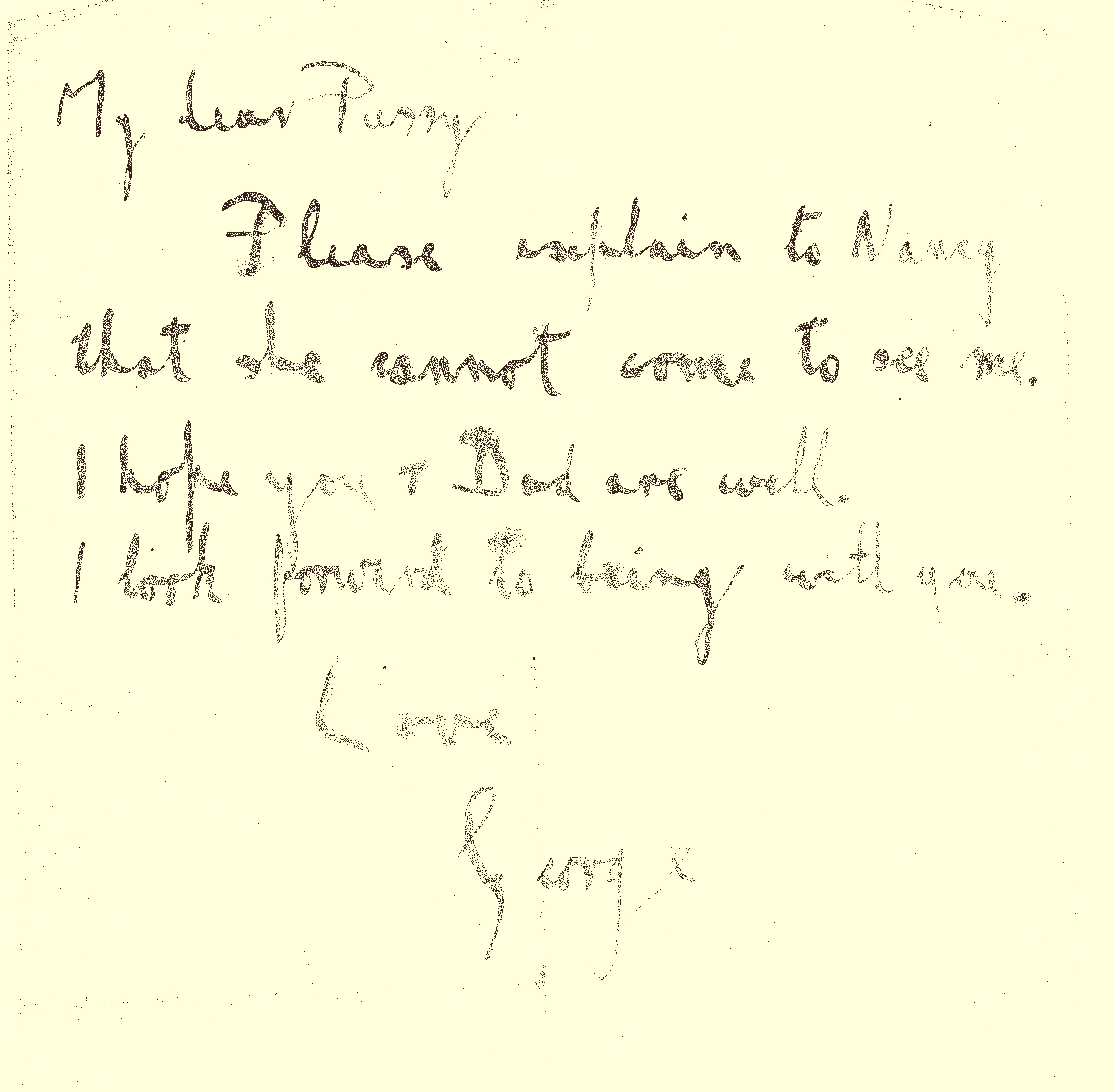

Writtten from Kingseat Hospital, May 1942

George Lloyd, recovering from PTSD, 1942

As a result of the accident, the young composer suffered terrible physical injuries and long-term psychological damage which, at that time, was diagnosed as ‘shellshock’, although we would now call these symptoms PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Lloyd was suffering from blackouts and shaking fits, enduring recurrent nightmares and the anguish of survivor guilt, as he relived his misfortune over and over again. He was sent to a Royal Navy Hospital near Aberdeen where the doctors concluded his condition was incurable. Worse, the fracturing of Lloyd’s mind and his inability to hold a pen meant that his career as a composer was in all likelihood over.

In the aftermath of his trauma, Lloyd had no wish for his wife Nancy to see him in such a dreadful state, so he wrote to his mother asking her to tell Nancy to stay away. But Nancy had other ideas, and she soon made the long journey to visit him. Nancy takes up the story in her own moving account.

I must tell you how I found him. He had lost control of his nervous system – his muscles had given way, and his locomotion was not functioning properly. His head was going from one side to the other, and his arms and legs were going all over the place. His body was full of large swellings, where the muscles had given way. His speech was slow and difficult to understand. After greeting him, he said:

‘Why did you come?’

‘Because I wanted to see you.’

‘I did not want you to come.’

‘Are you not glad to see me?’

‘No, and I don’t want you to come again.’

Before long I had to leave him to catch the bus to go back to Aberdeen. As I left, I said:

‘I’ll be back tomorrow.’

‘I won’t come to meet you.’ [He replied]

‘I'll come back every day until I see you.’

And off I went.

Despite their reluctance, Nancy eventually persuaded the doctors to discharge George to her care, imposing on him a strict regime of frequent rest, regular exercise and a healthy diet supplemented by vitamin pills. She started to read everything she could find about psychiatry and psychology, even learning the basics of hypnotherapy from her brother-in-law, the famous American psychiatrist, George Estabrooks. (Estabrooks specialised in the treatment of shellshock but worked in addition for the CIA developing methods of mind control.) As time went on, Nancy became an expert in homeopathic and alternative medicines, later achieving a worldwide reputation as a faith-healer. Meanwhile, Lloyd himself adopted positive thinking techniques, especially those outlined in Frederick Bailes’ famous book, Your Mind Can Heal You (New York, 1941). He also explored the theories of the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, giving detailed attention to his dreams and the prompts of his subconscious.

By following Nancy’s therapies, George Lloyd’s physical and mental state soon began to improve, although it would be over twenty years before the nightmares and his guilt ceased to haunt him. Most significantly, Nancy was determined that her husband should start composing again, so that creative work was another necessary part of his daily routine. After two years his hand was steady enough to hold a pen and, amazingly, just four years after his wartime injuries, Lloyd had completed two hour-long symphonies, the Fourth and Fifth, which showed no waning of his prodigious talents.

Professor Jonathan Davidson of Duke University, North Carolina has made a study of Lloyd’s healing process during those post-war years, and he believes that his creative work and especially the mental discipline of composition, were vital components in Lloyd’s return to health. The music of that period provides the best evidence. Anyone listening to Lloyd’s Fourth Symphony can sense that it transcends negative experience by means of a tremendous will power. The work is reminiscent of another war symphony, Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ No.7, which seems to grab victory from the jaws of defeat. Lloyd’s music captures both the danger and the excitement of combat in a work of fierce dramatic contrasts. Its slow movement expresses poignant loneliness and longing, placing the atmosphere of the remote Arctic seas alongside blissful reminiscence. The music attains rare heights of tragic feeling and compassion. The symphony’s expansive finale depicts a mighty struggle to impose order on chaos, culminating in a flag-waving burst of optimism. The triumph has been hard won and, when it arrives, there are goosebumps and spine-tingles in abundance. The crisis of the individual at war has become a jubilant crowd shouting ‘yes’ to life.

Lloyd’s Fifth Symphony is by comparison full of sunshine and smiles with a finale that can barely contain its high spirits. There remain moments of introspection, but the momentum towards joyful celebration is unstoppable. In truth, Lloyd’s recovery from his trauma was by this time far from complete, and he was still suffering periods of depression and panic attacks. Yet, where previously his prognosis had been bleak, now he felt able to describe the summer of 1946 as one of the happiest of his life. In understanding that claim, we should not overlook Nancy’s loving devotion towards him. Her carefully devised programme of rehabilitation and her belief in him as an artist were essential to the speed of his recovery.

What Lloyd did not foresee in the post-war years was the rise of musical modernism which marginalised him as a major British artist. He was not a man to resolve personal catastrophe or musical problems with intellectual theory, and he saw little value in the note-manipulating systems favoured by many modernists of the next generation. Lloyd believed that lyrical impulses and creative intuition were superior to logic and conceptual thinking, and he made a distinction between music that was ‘felt’ in the heart and music ‘concocted’ by the brain.

For Lloyd, even before his accident at sea, the symphony had always been a way to express psychological transformation and spiritual growth. Indeed, public reactions to his music have confirmed this view. The composer’s nephew William Lloyd recalls several occasions when medical professionals approached him after concerts to tell him how his uncle’s lyrical voice had provided comfort and stimulus to withdrawn patients. What had come from the depths of the artist’s psyche could penetrate deeply into the psyches of others.

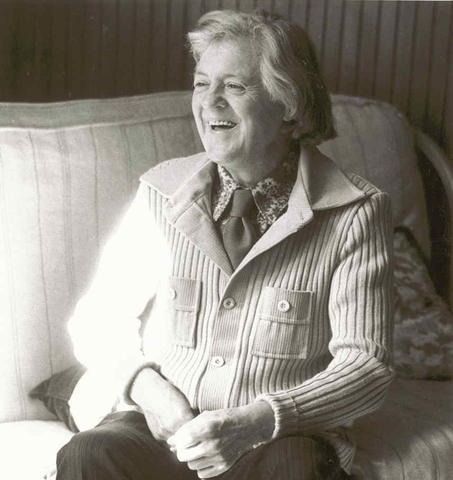

At 199, Clarence Gate Gardens, 1990

At 199, Clarence Gate Gardens, 1990

By the late 1970s Lloyd’s musical reputation underwent a renaissance, and more success would follow. Yet trauma revisited Lloyd in 1982, while he was living near Regent’s Park in London. On the 20 July, he was among the first to arrive on the scene after an IRA bomb exploded near the bandstand, killing seven bandsmen. The memory of the loss of his musical comrades on board HMS Trinidad must have made the scene of carnage especially painful. Lloyd’s response was to write a short piece, In Memoriam which paid tribute to the men lost that day. Yet, such was his psychological resilience, he continued producing spiritually optimistic works such as the Symphonic Mass (1991) which expressed his unorthodox Christian faith. His last symphony, the Twelfth (1989), written for the Albany Symphony Orchestra, emerged as serenely beautiful; the work of a man at ease with himself and full of octogenarian wisdom.

George Lloyd’s last composition, written as his own health was failing, was a Requiem Mass (1998) for choir and organ, dedicated to the memory of Diana, Princess of Wales. It concludes with a moving vision of divine light, the Lux Aeterna, which draws the dead towards eternal rest and consolation. Faith, mental discipline and a boundless appetite for life had permitted George Lloyd to grow beyond his horrific war experiences and the subsequent critical hostility to his music. The success of his later years, largely self-made, surely offers us all hope that music and creativity may not only heal our wounds but also make us complete as human beings.

©Peter Davison

1st August 2021

Further listening:

CD’s of featured works can be purchased at our on-line shop, but why not try our specially created playlist of Lloyd’s music,

Serene and Mindful, available on our YouTube Channel.

Further reading:

George Lloyd: Shaman or Showman? by Peter Davison

The broken man who created healing music. by Peter Davison

https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/developing-creativity-and-culture/arts-culture-and-wellbeing

https://musicpsychology.co.uk/music-and-wellbeing-links/

Shellshock in World War II - a documentary film.