Tuning Up - No. 3 March 2023

(revised October 2023)

Balzac’s Gambara:

By Peter Davison

Introduction

What should be the relationship between composer and audience? Should the composer’s personal spiritual quest prevail, regardless of the taste of the listener, or should the composer acknowledge that the audience may not share their subjective experience and seek some common ground? What is the effect of ambition, and the pursuit of fame and celebrity, in shaping the composer’s choices? In this article, musicologist Peter Davison explores these questions through the medium of Balzac’s Gambara, a short story about a composer whose idealism is slowly crushed by the cynical world that surrounds him. The story had a profound impact on Wagner and Schönberg, and through them on European musical aesthetics, particularly the shift to modernist forms, up to the present day.

Balzac's Gambara can be read, in translation, HERE.

Peter Davison writes:

Much of my fascination for the music of George Lloyd stems from sympathy towards his struggle against modernist orthodoxy in the period after the Second World War, when his accessible and tuneful style fell badly out of fashion. It has long been a puzzle to me why, during the course of the twentieth century, so many composers became alienated from their audiences, and why melodious music was so thoughtlessly dismissed as hackneyed and out of date. In 2001, I even edited a collection of essays called Reviving the Muse, which explored this thorny subject in some detail. But could composers like George Lloyd have been badly misjudged? Could his middle-of-the-road aesthetics and traditional values become newly relevant in our own times?

But what causes this continuing tension in our culture between old and new? I found some startling clues when I recently stumbled across Gambara, a story by the French writer Balzac. Its narrative accurately foreshadows many of the revolutionary developments in modern music, probing the moral, social and aesthetic controversies which define the modern era. My article explores Balzac’s prophetic tale, revealing a composer whose talent is wasted as a consequence of his flaws of character and the general ignorance of the public. Gambara’s tragic failure raises questions about the true nature of genius, exposing also how romantic art continues to influence our contemporary culture.

Balzac’s Gambara:

martyrdom, magic and the music of other planets

by Peter Davison

Balzac in 1842

Balzac in 1842

Among the most celebrated of French writers, Honoré de Balzac is best known for his epic series of novels The Human Comedy (La Comédie Humaine) which offers a forensic portrait of the pretences, struggles and disappointments of an emerging Parisian bourgeoisie. These voluminous texts are grimly true to life, but Balzac also penned stories exploring philosophical and theological themes. One such is Gambara (1837), an account of a gifted Italian composer living exiled in Paris just after the July Revolution of 1830. Despite his talent and great vision for humanity, Paulo Gambara is short of money because his idealistic worldview is consistently misunderstood by the society around him.

Gambara was originally commissioned by the Parisian journal, the Gazette Musicale, to promote Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots. The story’s narrative is subtle and complex, raising questions about the nature of genius and how art-music is conceived and evaluated. Balzac approaches his subject from many angles. Gambara himself vacillates between wanting music to be merely a source of pleasure and as a demanding means of spiritual elevation. Meanwhile, an Italian aristocrat, Count Andrea Casorini, who wants to support Gambara, argues that Beethoven is the most progressive composer of instrumental music, able to convey the highest ideals. Rossini’s music, he asserts, is by comparison mere vulgar entertainment. Although Gambara considers himself a successor to Beethoven, he decides to defend Rossini’s delightful and memorable tunes. He reminds the Count of the debt German music owes to Italian musicians, berating him for his extreme opinions. Music, according to Gambara, should be a seamless blend of sensuality and intellect, feeling and form, spontaneity and structure.

Balzac describes the Count as if he is playing an operatic role. Foppish and insincere, his real motivation is to seduce Marianna, the composer’s beautiful and long-suffering wife. She adores her husband for his brilliance, even though he expects her to make all manner of sacrifices to sustain him. She must act as his lover, mentor, manager, breadwinner, muse and mother. Count Andrea’s financial generosity makes Marianna obliged to him. He liberates her from the responsibilities that have bound her to Gambara. Over the years her patience has worn thin, since her husband is unwilling to dilute his idealism to obtain publication or performances. Indeed, when Gambara plays his music privately at the piano, he soon loses touch with reality. In this instance, the line between genius and madness is particularly narrow.

"There was no hint even of a poetical or musical idea in the hideous cacophony with which he had deluged their ears; the first principles of harmony, the most elementary rules of composition, were absolutely alien to this chaotic structure. Instead of the scientifically compacted music which Gambara described, his fingers produced sequences of fifths, sevenths, and octaves, of major thirds, progressions of fourths with no supporting bass,—a medley of discordant sounds struck out haphazardly in such a way as to be excruciating to the least sensitive ear."

After this puzzling scene, Balzac describes Gambara’s face as ‘radiant, like that of a holy martyr.’ We must imagine music so complex that it cannot be followed, and yet its details possess a remarkable similarity to the abstract play of intervals found in Debussy’s Twelve Studies for piano, a work written eight decades later.

Debussy Douze Etudes

As the story unfolds, time after time, the reader is struck by Balzac’s prescience. He anticipates the aesthetic debates that would first preoccupy romantic composers and then the radical modernists of the next century. At a key moment, Gambara is taken by Count Andrea to a performance of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s new opera Robert le diable (Robert the Devil), notorious for its spectacular musical and theatrical effects. The Count ensures that Gambara is intoxicated, stimulating his senses but blunting his intellect. The composer is initially transfixed by the work’s drama and sublime music - yet the next day, when he has sobered up, he considers the score a random sequence of worthless effects.

Overture to Robert le diable

By highlighting the conflict between Italianate light-heartedness and Germanic heft, between Robert le diable’s showy theatrics and Beethoven’s inward seriousness, Balzac anticipated the notorious polemic which Richard Wagner would launch against Meyerbeer, who was the doyen of French Grand Opera. Wagner had first visited Paris in 1839 to secure performances for his operas, unfairly blaming Meyerbeer for his lack of success. Yet, during his time in the city, Wagner did achieve some renown as an author of criticism and journalistic pieces, even writing a novella for the Gazette Musicale, the original publisher of Gambara. Wagner’s fictional memoir A Pilgrimage to Beethoven describes how a young composer arranges to meet his idol in Vienna. In 1841, Wagner penned a sequel, An End in Paris, chronicling the same young composer’s untimely demise. The narrator’s tone is despairing and surely owes a debt to Balzac’s Gambara.

"Who knows what died in this child of man, leaving no trace behind? Was it a Mozart, - a Beethoven? Who can tell, and who 'gainsay me when I claim that in him there fell an artist who would have enriched the world with his creations, had he not been forced to die too soon of hunger?" Richard Wagner in Paris 1842 by E.B Kietz

Richard Wagner in Paris 1842 by E.B Kietz

By the time of his second visit to Paris in 1850, Wagner’s waning enthusiasm for Meyerbeer had turned to complete hostility. In his writings and public statements, Wagner now upheld the German music of Bach and Beethoven as the only true path, criticising the fusion of national styles and superficial effects which prevailed in French Grand Opera. Of course, Wagner knew as well as anyone how to deliver a coup de théatre, and he had absorbed many eclectic influences. To that extent, his polemic was driven as much by grievance as any significant aesthetic differences with his rivals. Nonetheless, Wagner’s symphonically integrated music dramas possess a strong German identity, while also conveying a numinous quality and intellectual seriousness largely absent from the works of his contemporaries.

Wagner’s fate continued to imitate Balzac’s art. The fictional Gambara composes a series of operas exploring religious themes, including one based on the life of Mohammed which is described in detail and performed at the piano by the composer. Gambara’s identification with the founder of a world religion, a prophet and a political leader, reveals his limitless spiritual ambition, while also reinforcing his status as an outsider, unallied to any single nationality, faith or musical style. He considers himself the Messiah of his musical generation, foreshadowing in real life Wagner as a cultural phenomenon who himself had at one time planned an opera based on the life of Christ. It has also been suggested that the multi-opera concept of Wagner’s Ring Cycle may have originated from Balzac’s story.

Wagner, unlike Gambara, became unimaginably successful. It could so easily have been different, as he drove his first wife Minna to distraction with his infidelities and money problems. He was however able to avoid Gambara’s miserable fate because of his ruthless ambition. An unscrupulous personality, Wagner never denied himself anything if it furthered his creative vision. In later life, backed by Ludwig II of Bavaria and with a new wife, stolen from a trusted colleague, Wagner combined ambition and ideology, innovative musical technique and managerial skills, so that a cosmopolitan elite were soon kneeling before him. By contrast, Gambara’s neediness causes him to hesitate at crucial moments, succumbing to unrealistic fantasies and lacking the confidence to face the world around him.

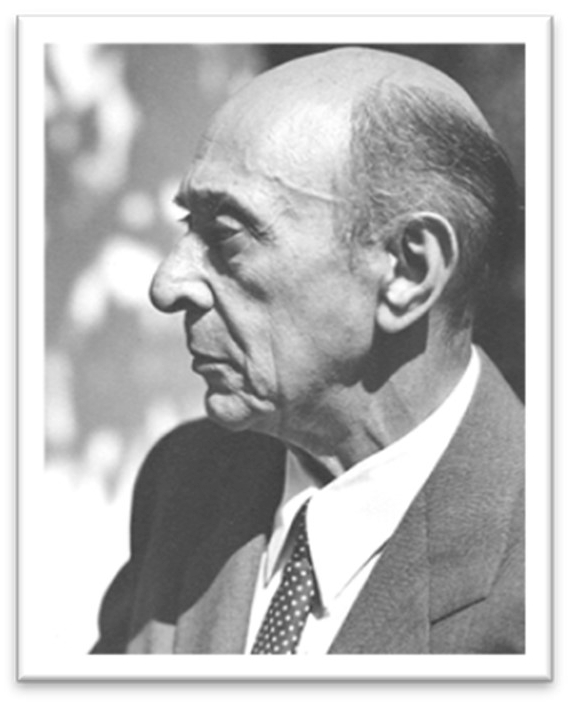

There are yet more historical resonances in Balzac’s story as the twentieth century approaches. The Jewish Austrian composer and theorist, Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951), was an eager follower of Wagner and believed wholeheartedly in the supremacy of the German musical tradition. He was fond of referring to Balzac in his musicological writing, and he must surely have read Gambara. We know too that he admired another Balzac story, Seraphita, about the final days of an androgynous sage, during which he/she is transformed into a spiritual being who prepares to leave the material world. Seraphita’s experience concurs with the mystical theology of Emanuel Swedenborg (1682-1777), who claimed his prophecies were dictated directly to him by Christ. In Seraphita, Balzac summarises Swedenborg’s description of heaven, where there is no time and space, nor any separation of the opposites. Instead, essences and ideas exist in static form, and it is the moral condition of the soul that dictates proximity to the divine. From these metaphysical insights, Schönberg invented the rules of serialism because, in the transcendent realm, there is no up and down, no backwards and forwards, so that a note-row can be reversed or inverted without losing its essential identity. Schönberg, like Gambara, considered that his most ambitious music existed in a purely spiritual dimension beyond the limitations of earthly existence. It was thus no longer bound by the rules of harmony, including such notions as consonance and dissonance. Gambara states:

"My music is good. But as soon as music transcends feeling and becomes an idea, only persons of genius should be the hearers, for they alone are capable of responding to it! It is my misfortune that I have heard the chorus of angels and believed that men could understand the strains."

In 1933, while living exiled in Paris, Schönberg returned to the Jewish faith. He had always cultivated the persona of an Old Testament prophet issuing commandments from the mountain top, echoing Gambara’s identification with the Abrahamic tradition. Jehovah is not a compassionate God, but a God of judgement, jealous rage and harsh punishment. He condemns humanity’s weaknesses, creating a conflict in the human psyche between earthly needs and spiritual aspirations. It was a split Schönberg could not resolve, as his final unfinished opera, Moses und Aron (1932) reveals. Moses, the spiritually aloof prophet, struggles to express his esoteric truth, while Aron communicates naturally with the Israelites because his lyrical gifts appeal to their senses. The historical battle between intellect and emotion, form and expression, spirit and matter had reached an impasse, as Schönberg came to epitomise the alienation of the artist from a mainstream audience; the result of an extreme modernist ideology which had stripped music of its appeal to the senses.

Arnold Schönberg 1948,courtesy of University of South Carolina

Arnold Schönberg 1948,courtesy of University of South Carolina

A decisive moment in Schönberg’s creative development had been his symbolical release from the bonds of tonality which occurs in his Second String Quartet (1908), a work that emerged after the breakdown of the composer’s marriage. Its vocal finale is a setting of ‘Rapture’, a poem by Stefan George, which likens the experience of transcendence to breathing the ‘air of other planets’. At the movement’s opening, chromatic figurations seemingly float free of any harmonic root.

Finale of Schönberg's String Quartet No.2

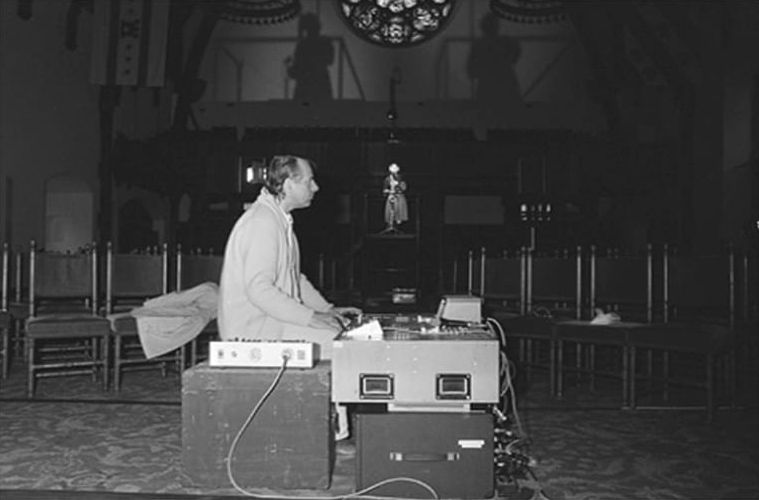

After 1945, the German champion of the avant-garde, Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) tried once again to create music from outer-space, poised at the console of his Cologne electronic studio, imagining himself in telepathic communication with beings from the Sirius star-system. Behind the science fiction was a persistent belief in the composer as a priestly magus, the manipulator of mysterious sounds who channels a metaphysical reality beyond ordinary human comprehension.

This desire to create the transcendental music of the future reveals a curious parallel between our spiritual longing to reach the heavens and humanity’s more literal ambition to reach the stars. Technological progress has made space travel a reality, while also unlocking new realms of musical sound. We are reminded of Gambara’s claim that ‘whatever extends science enhances art’. This was his statement of faith in the creative potential of improved and new musical instruments, including his own Panharmonicon, a type of organ capable of reproducing the colours of the romantic orchestra and even the human voice. Balzac thus anticipated the invention of the electronic synthesiser which empowered individual composers to create seemingly limitless sound-worlds, allowing them to travel to metaphorical planets of their own invention.

Karlheinz Stockhausen during a rehearsal in The Hague, 1982

Karlheinz Stockhausen during a rehearsal in The Hague, 1982

A Faustian pact with science and technical innovation encourages the delusion that humanity can escape the restrictions of earthly existence, loosening our grasp of reality. The devil commands the material world, manipulating appearances and exploiting human fears to spread chaos. Perfect for the plot of an opera, you might think, and in Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable, the plot concerns the recovery of order and truth. Robert’s father, the Devil, tricks his son into losing his beloved, then tricks him again into using magic to win her back. Truth, it turns out, is synonymous with faith in the Christian God who exposes the whole diabolical deception. But ultimately, the spider weaving this web of deceit is Meyerbeer himself. He cleverly underpins the unfolding drama with powerful musical rhetoric, and his audience is willingly seduced by the spectacle of heroic deeds and the glamour of the occult, including a titillating ballet danced by the ghosts of lecherous nuns.

Dance of the ghostly nuns

Theatre and music have long been used as means of emotional manipulation. A suitable musical accompaniment can transform even the vaguest narrative into metaphysics; a promise which must inevitably disappoint, since there can be no short-cuts to spiritual truth, love or beauty. Talented composers of opera have an instinct for theatrical effect, provoking boundless fantasies in their listeners, transporting them to alien planets that rob them of their earthly humanity. Yet such a rapturous response quickly fades, if a composer’s aim has not been to educate but to entertain, as Gambara himself discovers after hearing Robert le diable.

Even Wagner is not above suspicion. Debussy referred to him as ‘Old Klingsor’, the evil magician from his music drama Parsifal, while Friederich Nietzsche, once Wagner’s most devoted follower, came to believe that his former idol reduced listeners to an unhealthy hyper-emotional state.

"Wagner’s art is sick. The problems he presents on the stage – all of them problems of hysterics – the convulsive nature of his affects, his overexcited sensibility, his taste that required ever stronger spices, his instability…all of this taken together represents a profile of sickness that permits no further doubt…"

Nietzsche eschewed Wagner’s bombast and intoxicating power, growing instead to admire the emotional realism of Bizet’s Carmen in which love and its actors are stripped of any idealisation. In truth, Nietzsche’s attitude towards Wagner remained ambivalent, paralleling Gambara’s equivocal response to Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable. Are we deceived by Wagner, or is he revealing a hidden truth that challenges our mundane and conventional assumptions?

We must certainly be aware that intensity of musical expression is no guarantee of profundity. It is easy enough, after all, to confuse a strong visceral impact or an unusual sound with meaningful substance. If the senses are over-stimulated, and listeners are denied the formal limits associated with classical composers such as Beethoven, Haydn and Mozart, we are all too easily engulfed by sentimentality. But equally, if formalism is taken too far and, as in Schönberg’s serial works, music lacks a sensual dimension, what we hear stays forever beyond our grasp.

Great art should guide us towards better rather than perfect ways of being. It should inspire and elevate without making us feel banished into stupidity by intellectual elites. Yet so often the gap between the artist’s vision and the surrounding culture is experienced as an unbridgeable gulf. We feel that the wider culture has grown insensitive, atrophied and cynical or that an overly sophisticated artist has lost touch with reality. Who is to blame? Undoubtedly our culture has grown fragmented, confused and materialistic, yet the aggressive and revolutionary gestures of extreme modernists, attacking audiences as ignorant, indifferent and hostile to new ideas have not proved effective. In that sense, the split between artists and audiences has become self-perpetuating, a culture war that never ends. The example of Wagner is perhaps an unlikely exception, showing that sometimes the revolutionary genius can win the upper hand, reshaping the collective culture to his own ends. It is an iconoclastic path that is hard even dangerous to follow, and which all too easily overlooks Wagner’s own resolution of the conflict between his romantic individualism and the limitations of the collective culture. After all, in his final music drama, Parsifal, Wagner reinforced enduring religious principles and affirmed traditional aesthetic laws, leaving behind the transgressive music and revolutionary ideas found in earlier works such as Tristan and the Ring Cycle.

Returning finally to Gambara, the story concludes tragically, focusing our attention on a consistent theme of Balzac’s writing, that the price of ambition is the loss of love. Marianna, having eloped to Italy with the Count, returns to Paris to be with her husband. Her youth and beauty have faded, and she has been humiliated by the Count who has married a ballet-dancer. In the meantime, Gambara has been stripped of everything, fulfilling his desire for martyrdom. His scores are used as wrapping paper by local shopkeepers, while he and Marianna are forced to busk in the local park just to survive. People listen but believe the music they hear is by Rossini not Gambara. And yet the couple now know that their love is genuine, if only because they have lost everything else.

Balzac leaves us in no doubt that, despite a virtuous and respectable façade, bourgeois society is a theatre of illusion, a Grand Opera if you like, that fuels ambition and greed, exacting a high toll in human suffering. The Count’s betrayal of Marianna reflects a more general attitude - that one may speak of high ideals but still treat life as a game, in which love is an amusement and a woman merely a toy.

Is an idealistic artist any different if, by aspiring to boundlessness and unobtainable beauty, visions not of this world, he forgets human love and the attentiveness it demands? The stormy private lives of Beethoven, Wagner and Schönberg remind us that genius and the devotions of love are not easily reconciled. The lesson is a hard one for Gambara, reflected in his final utterance.

"Water is a product of burning."

Gambara’s desire to reach for the highest spiritual ideals, and his willingness to leap into the flames of his creativity, lead only to floods of tears, both his own and those of his wife.

© Peter Davison March 2023 (Revised October 2023)

This article can be downloaded in PDF Format HERE: