George Lloyd’s music is not ‘Romantic’, or even ‘post-Romantic’. Both those genres are usually associated with the early and late 19th century, whereas his music is without doubt 20th century music, but it ‘sounds like’ music from an earlier period because throughout his life George Lloyd remained loyal to conventional notions of melody, harmony, and counterpoint. He repudiated atonality, serialism and the avant-garde composition techniques which came to dominate classical music during the last century.

This reluctance to abandon romantic and late-romantic norms was unusual among 20th century composers, and his music attracted some harsh criticism. Lloyd’s conviction that the avant-garde was merely a passing fashion appeared to be a lost cause in the light of the great cultural shift in European aesthetics which took place in the first two decades of his life. In 1913, the year he was born, Schoenberg had already composed his first atonal work, and Stravinsky’s ballets, The Firebird and The Rite of Spring had opened the way to asymmetrical rhythms. In European painting, Picasso and Braque were developing the style known as Cubism, which included Picasso’s ground-breaking Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In literature, Ezra Pound and James Joyce were extending the boundaries of language and, while Lloyd was still an infant, the Cabaret Voltaire launched its Dadaist rejection of elitism and traditional aesthetics in favour of literal nonsense, absurdity, and anarchy. In psychology, Jung and Freud had revolutionised the understanding of the human mind with the discovery of the unconscious.

In this context, it was inevitable that Lloyd’s romantic style, with its expressive melody and rhythm, lush orchestral textures and extended Sonata form movements with repeated false endings and grand finales, would be judged by modernist critics and academics to be regressive and anachronistic. The question arises as to why Lloyd should have remained so unmoved by the radical changes brought about by Modernism in music. The answer may be found in his lack of schooling and formal education, which allowed him to be more fully immersed in the romantic outlook of his unconventional family, who pursued a bohemian creative life at the centre of the St. Ives artists’ colony.

The Lloyd family had settled in St Ives in 1895, in the early days of that colony and, for the next 40 years (until George was 22), their lives revolved around playing music, painting, writing poetry and archaeology, an environment further stimulated by George’s mother’s fascination for Celtic mythology and his father’s obsession with Italian opera. The playlist sequence Echoes of Romanticism explores the visual imagery of that culture. A world of stone circles, archaeological treasures, folk tales and ‘the Fairy Faith’, the spiritualism of Theosophy, the seascapes and figurative art of the St. Ives and Newlyn Schools of painting, as well as strong international influences drawn from Europe and the USA, surrounded the young composer.

That mosaic of cultural heritage had one unifying factor – the romantic tradition which emerged as a reaction against the rationality of the 18th century Enlightenment, leaning instead towards individualism, emotion, and the imagination, characterised by the celebration of nature and landscape, the idealisation of the Middle Ages, the cult of the ‘noble savage’ and the value of craftsmanship, driven by a reluctance to follow the crowd.

George Lloyd shared with Romantic artists and composers a sense that Nature was a source of inspiration, beauty, and spiritual renewal. He believed that his music came from his feelings and emotions, not merely from the manipulation of notes by the intellect according to a pre-determined theoretical system, or from iconoclasm and novelty. His was a practical as well as an imaginative preference. After all, he would spend twenty years as a market gardener, keeping bees, and cultivating flowers, vegetables, tobacco and mushrooms. He had a long association with alternative spirituality and the supernatural, following daily rituals of prayer, meditation and the reciting of mantras. He used several methods of divination, including the Chinese oracle, the I Ching, water divining (or dowsing), and observing the movements of a pendulum. He insisted that his use of these techniques was based on his personal experience of their success, while acknowledging that science had no explanation for such irrational processes. He believed that his music came directly from his subconscious, although he knew that success in composition always requires good discipline and rigorous technique.

George Lloyd’s unusual education certainly influenced his decision to swim against the tide of cultural change. Due to recurring episodes of rheumatic fever, he did not go to school at all until he was twelve, and two years later in 1927, at the age of fourteen, he demanded a specifically musical education. He attended Chichester Cathedral School, where he acquired a basic grounding in traditional harmony, counterpoint and singing, before continuing his studies at three of the principal London colleges (The Royal College, The Royal Academy and Trinity College.) His student paperwork shows that his preferred teachers were all specialists in the late-romantic style. He made detailed tables comparing the ‘rules of music composition’ which each of them proposed in their textbooks and concluded that, because they disagreed about almost all those rules he should rely on his instincts and go his own way.

Echoes of Romanticism – a summary of playlist themes and images

1. Frances Lloyd: American and European painting.

The engagement of George Lloyd’s father and grandmother with the St. Ives artists’ colony brought the young composer into contact with diverse nationalities, social classes, and cultural and political interests. His American grandmother, Frances Lloyd, had trained as an opera singer in New York, appearing there in Gounod’s Romeo et Julietta in 1875. The following year she moved to Paris to study painting in the studio of Henri Lucien Doucet, where she met and married George Walter Lloyd, a retired Royal Navy Captain. They moved to Rome, where their son William, George Lloyd’s father, was born, and they lived there until Walter died in the great cholera pandemic of 1889. Wishing to raise her son as an Englishman, (presumably unaware of Cornish nationalism) she joined the budding artists' colony in St. Ives, a few years after Julius Olsson had founded the first art school there, which had become well known in Europe through several exhibitions in Paris galleries. In St Ives she lived in the same lodgings as Louis Reckelbus, from whom she learned to use the medium of tempera, thereafter painting landscapes and spiritual subjects, including allegorical interpretations of the discovery of the Andromeda galaxy and paintings of the Nine Muses.

Frances was the daughter of one of the most prominent painters in the USA, William H Powell, whose work included two large scale historical murals for the USA Capitol building in Washington D.C., and nationalist images of evictions during the Irish potato famine (right.) Powell studied under Henry Inman and Samuel Morse in New York, and associated with the American Romantic landscape painters of the Hudson River School, represented by the monumental allegorical canvases of Thomas Cole. Frances had grown up among these painters on the New York city arts scene, and returned there to live from 1902 to 1909, when she gave lectures to the New York Theosophical Society before returning to Zennor,

2. William Lloyd: The Arts Club, St Eia and Italian opera.

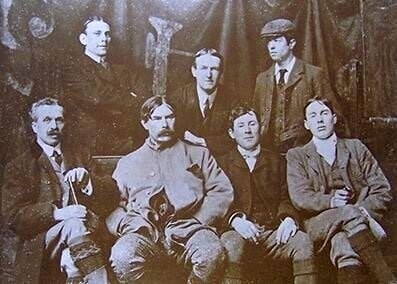

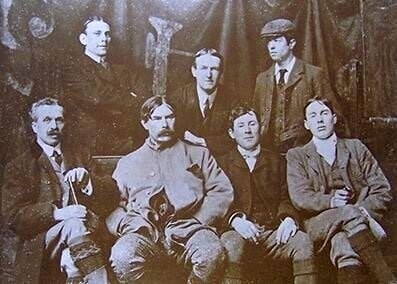

Frances’ son William also took up painting before turning his attention to writing. He became an opera afficionado, travelling to London as frequently as he could, and several times to Italy to hear great singers. With his mother he kept an album of articles on opera and the singers they had heard and, in 1908, he wrote a biography of Italian composer Vincenzo Bellini. Italian opera in the 19C was characterized by its emphasis on expressive melody (bel canto) and vocal skill, aiming to provoke strong emotional responses from the audience by means of dramatic narratives. Productions used elaborate sets and costumes to enhance virtuoso performances by highly trained soloists. William instructed his young son in the style, giving him scenes from Shakespeare to set to music, first in the style of Verdi and again in the style of Puccini. William Lloyd was Secretary, and later President, of the St Ives Arts Club, the social centre of the artists’ colony, (left) and Vice President of the Penzance Orchestra. Frances’ son William also took up painting before turning his attention to writing. He became an opera afficionado, travelling to London as frequently as he could, and several times to Italy to hear great singers. With his mother he kept an album of articles on opera and the singers they had heard and, in 1908, he wrote a biography of Italian composer Vincenzo Bellini. Italian opera in the 19C was characterized by its emphasis on expressive melody (bel canto) and vocal skill, aiming to provoke strong emotional responses from the audience by means of dramatic narratives. Productions used elaborate sets and costumes to enhance virtuoso performances by highly trained soloists. William instructed his young son in the style, giving him scenes from Shakespeare to set to music, first in the style of Verdi and again in the style of Puccini. William Lloyd was Secretary, and later President, of the St Ives Arts Club, the social centre of the artists’ colony, (left) and Vice President of the Penzance Orchestra.

Following an inheritance from a childless uncle, William purchased Julius Olsson’s house, St Eia, a substantial thirteen-room dwelling overlooking St Ives town and Carbis Bay. What had been Olsson’s large studio became a regular weekly meeting place for the musicians of the area, large enough to accommodate a small orchestra. George Lloyd was born and grew up at St Eia, surrounded by Olsson’s paintings, international visitors, and weekly chamber music concerts.

3. Constance Lloyd: Arts and Crafts and the Celtic Revival

Constance Lloyd, George’s mother, was half Irish. Her grandfather Philip Dwyer was known as ‘the historian of County Clare.’ He was a Canon of the Church of Ireland, who emigrated with his family to Vancouver Island as a missionary before settling in Yorkshire. Constance immersed herself in her Irish heritage, and engaged with the Celtic Revival, learning to speak Irish and visiting Dublin several times during her research. She collected the works of Anglo-Irish playwright, folklorist and musician John Millington Synge, and books on Irish folk tales and mythology. She corresponded with Douglas Hyde, who was later to become the first President of the Irish Republic, comparing Irish and Cornish folklore.

A follower of the Arts and Crafts movement, she tried her hand at weaving, creating heavily textured and embroidered homespun fabric, and had a collection of brass, copper and pewter crafted by members of the Newlyn school. She collected pottery by her friend Bernard Leach, who had moved to St Ives in 1920, and his pupil Michael Cardew, and she commissioned work by the young furniture maker, Robin Nance. She befriended Gypsy people and even as a young woman, despite her background among the gentry, she spoke some Romany, and from 1924 when the family moved to Zennor, she would invite the Gypsy hawker women into her house for tea (scandalising other residents) and would be seen in the village wearing a headscarf and smoking a pipe.

4. Mythology and the fairy 'otherworld'

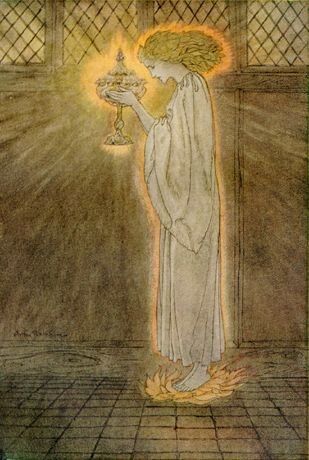

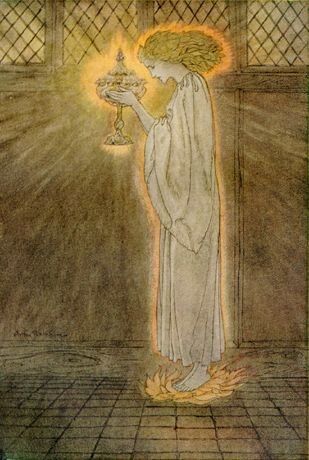

George’s mother and older sister regularly read to him from The Faery Faith, and Cornish Fairy Tales, and from several books illustrated by Arthur Rackham, including Irish Fairy Tales, English Fairy Tales and Wagner's The Ring of The Nibelung. George's brother Walter recalled that their mother could recite the stories from the medieval Welsh Mabinogion from memory, and her library at St Eia included the Theosophical fantasy novel. The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed, (1914) which is a reworking of those tales. The romance of the Celtic Revival is represented in the playlist by several paintings by Arthur Rackham (left) and John Duncan, including The Riding of The Sidhe, (below right) which combines in a single painting Celtic decorative styles and reverence for horses, the Faery faith, contemporary archaeological discoveries, tempera technique, seascapes, fine goldwork and jewellery, the Arts and Crafts movement, Jung’s subconscious archetypes and Symbolist art.

5. Folk culture: the hero myth, and the nobility of naivety

The Romantic movement embraced pre-industrial history, folklore, and mythology. The bardic poetry of Ossian helped to establish the Romantic tradition, becoming a best-seller which swept through Europe. That fashion for all things Celtic endured and, 170 years later, George Lloyd’s first opera Iernin was written and performed in London’s West End when he was only twenty-one. The opera was based on an ancient Cornish folk myth in which a fairy creature falls in love with a Celtic warrior hero, who must then choose between his new love or his duty to defend his people against the invading Saxons. The libretto and the score made deliberate use of folk motifs, particularly in the crowd scenes.

6. Cornish landscape and archaeology

George Lloyd’s parents were keen archaeologists and founder members of the West Cornwall Field Club which carried out the first excavations of some of the Bronze Age megalithic monuments and Iron Age settlements in the area. They were the founders and curators of The Wayside Museum in Zennor, which included stone-age artefacts. George himself stated that the ‘romance of the stones’ and the colours of the gorse and the sea got into his music, remaining indelibly fixed in his mind throughout his life.

“The colours of Cornwall have meant an enormous amount to me and still do. Those colours which I saw without knowing what I was seeing - that very blue, almost Mediterranean sky … because our house was overlooking St. Ives Bay, and you know how beautiful it is…so you’ve got all that wonderful blue, the extraordinary luminosity of the area, and then on the hills and the moors there was this wonderful gorse and heather colour - that is what I was brought up with. And I wandered about the moors and looked at the stones and I saw everything and everything was very, very vivid to me, and I used to have a funny sort of feeling about all those stones. In somewhere near the beginning of the opera the hero, Gerent, he says to the baritone ‘Almost these stones seem to have life for me you know’ and I really felt the same sort of way.” (Interview, Chris De Souza)

In the notes to his Symphonic Mass (1992) he recalled that, as he wrote the work, images of Celtic and Saxon jewellery repeatedly came into his mind, and he commissioned an image based on his description to serve as the album cover.

7.Intuition, the Muse and the subconscious

Romanticism has been described as ‘the rebellion of the heart against the head’, and George Lloyd’s distaste for purely intellectual or logical systems of composition reflected his preference for communicating a sense of awe and the sublime. The pursuit of beauty and psychological truth were among his central concerns, and he trained himself to respond to his intuition, which provided a ‘clue’ as how to elaborate his musical ideas. He and his wife Nancy studied the writings of the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung in some depth, seeking innovative ways to heal George’s mental trauma caused by his wartime injuries. His revisiting of the mythological images of his childhood, derived from Theosophical and Celtic sources, resonated with the new theories about the subconscious developed by Jung, who had begun creating his Red Book in the year George was born. While there is no evidence that the Lloyd family attended Jung’s influential series of lectures at nearby Polzeath in 1923, the influence of Jung’s thought in Cornwall underlines the suggestion that George Lloyd was raised in a culture in which spirituality, emotion and personal inspiration were central to his aesthetic experience.

8. Representational and figurative art -

The St Ives and Newlyn Schools

The representational art of the St Ives School of painters has been somewhat overshadowed by the opening of the St. Ives Tate Gallery in 1993. Nevertheless, the figurative artwork of the earlier School, particularly the extraordinarily accomplished seascapes and realist depiction of the local fishing culture brought representation art to a new level in Britain, and the genre has stood the test of time, being much sought after by art dealers. One of these painters, the American Paul Dougherty, was a close friend of the Lloyd family, and in 1913, the year George was born, he and Will Lloyd travelled to Switzerland, where he made several paintings of The Matterhorn, one of which hung in George Lloyd’s study alongside Dougherty’s seascape of rocks off Zennor Head. Painter Stanhope Forbes, the ‘father of the Newlyn School’ was a friend and guest of the Lloyd family and wrote admiringly of George Lloyd’s music.

Summary

The interests, ideas, pre-occupations, and history of George Lloyd’s immediate family in St. Ives marked them out as true romantics. That background had a lasting effect on the young composer, whose unusual temperament and unorthodox education allowed him to master a traditional musical language which was then transformed by a strong individuality. He kept one foot in Romanticism and the supernatural fairy world, while planting the other in solid technique and practical application. He was intensely disciplined about his daily routine, including his compositional work and the management of his business, while taking great trouble to cultivate and maintain his relationship with his Muse, the subconscious origin of his musical inspiration.

As one British journalist remarked in 1996:

“It is untrue to say that they don’t write music like that anymore. They Do. George Lloyd does.”

William Lloyd

January 2024

|